Memory, she thought, is

a sacred place. It is the place where the past is gathered—an inner synagogue

where we make meaning of our existence.

You know those books

that just make you giddy because they are soooooo good and the author is SOOOO

smart and you are just happy you live in a world where words can be outfitted

to paint a splendid, moving, remarkable heart-stopping portrait of love and

life and hope and ache and power?

You know those books that just tug you into them and hold you

tightly so that you look up and are surprised that you are on the subway and

not sitting across from characters whose tongues drip simple wisdom and who are

salt and light and everything that is flawed and flourishing about humanity?

After Anatevka is that book.

It is a globe, a sphere, one of those snowglobes you shake peering into

the tiny world crafted perfectly and shrouded in flickering snowflakes. It is a

capture of a moment of exquisite heartbreak against a brutal yet achingly lovely

canvas that can never quell that which you cannot tether from a human: faith,

hope, the best kind of once-in-a-million love.

After Anatevka is that book.

It is a globe, a sphere, one of those snowglobes you shake peering into

the tiny world crafted perfectly and shrouded in flickering snowflakes. It is a

capture of a moment of exquisite heartbreak against a brutal yet achingly lovely

canvas that can never quell that which you cannot tether from a human: faith,

hope, the best kind of once-in-a-million love.

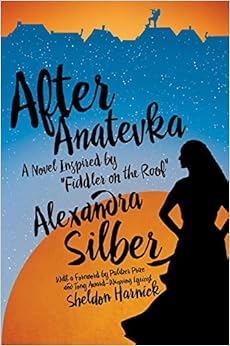

After Anatevka

answers a question I revisit every time I see a production of Fiddler on the

Roof: what happens after Hodel leaves Anatevka with the news that her beloved,

the radically smart Perchik, has been transported to a Siberian prison?

The door on her story is closed at the train station as she explains

why she will go far from the home she loves to follow Perchik while her father

Tevye, is confronted with one more way that the traditions of his past and his

religion are fraying at the seams.

I thought this was a fascinating premise for a novel and I

couldn’t wait to get my hands on a copy.

What I wasn’t expecting, however, was to encounter one of the smartest

historical novels I have read in an age nor one of the most lyrical debut voices

of my reading life.

After Anatevka, is not a story so much as an experience and

in lesser hands it could never embroider the pathos and light of a historical

narrative tradition to create a melancholy

and everlasting tapestry of hope.

Yes, hope. For all

the darkness undercutting Hodel’s imprisonments and Perchik’s suffering in the

Siberian salt mines, the power of hope and the commitment to life ( hear L’Chaim!

in your head) is the true theme of the story.

Love knows no barriers. Love is a spiritual connection .Love has agency

beyond borders and boundaries, deceit and despair.

The bookrepresents Hodel and Perchik’s present: first Hodel incarcerated as a single woman in pursuit of her fiance in a kind of holding cell ( held in time and place at the mercy of waiting ) and then reunited with Perchik in Nerchinsk with respective flashbacks subverting every trope of romantic ballads with startling freshness. It is in flashbacks that Silber is at her most ingenious:

colouring in the world of Hodel and her sisters and infusing a crash course in

cultural norms in early 20th Century Russia. A treatise on the beauty of domesticity and

the advocacy for women who think beyond the realm of their small town and

customs are balanced to justify all female experience. The feminine sphere –

either perfecting the baking of the challah or pursuing a man outside of your

faith ( Chava) are seen as equal experiences and all worthy. In the latter half of the book, Perchik’s

story is embroidered—and taken beyond the seams of anything grounded in its

many nods to its theatrical counterpart and into Silber’s own imagination. While Hodel’s limitations are dictated by

the rubrics of a woman’s place in Anatevka, so Perchik finds poverty and mental

abuse by his uncle the chains that would keep him from pursuing life. And all while peeling back the curtain of

their formative years, Silber forms the perfect pair--- allowing the reader to

fully understand why Hodel would leave the safety of her home for a life of

destitution and darkness and why Perchik pursued a forbidden dance with the dairyman’s

daughter in a small village.

Their connection is palpable and bursts off the page. Even while Hodel is drawn to the past:

remembering, fingering through letters late delivered from her sister Tzeitel,

we see that there was no other choice but for her to chase one half of her soul—Perchik---no

matter the consequences.

A large portion of the book follows the (expertly researched

) daily life of internment at a labour camp.

Into this world, Silber broadens the circle with fluid, dimensional

characters – both overseers and fellow prisoners—that add colour, human and

life to its dreary toil.

I just cannot say enough about this book. It is a

world. Silber’s instincts are pitch

perfect, drawing you in and tethering you to a tale remarkable in its praise of

the fortitude of spirit and intelligence.

Modern parallels ( the best aspect of historical fiction), encourage the

reader to ponder how far they would go to speak and be heard. Faith is at the crux of Hodel and Perchik’s

love, even as they find it beyond the metrics of the traditions that Tevye saw

slipping from his family in the source musical. And all unfurling in an expertly woven tale

full of self-awareness and beautiful language.

“The pivot?” Hodel murmured.

“The fulcrum. The turning point. In every story there is

always a moment when the anchoring thread of the tapestry unravels. I don’t know that I have ever been inside that

story until now.”

“There is a kind of transaction that occurs between a person

and a place: you give the place something and it gives you something in return. In years to come, Hodel would know for

certain not only what Nerchinsk had taken, but what it had given her as well.”

For theatre buffs, this book will excite you – yes, it does have several lovely nods to the musical so beloved. But for readers with no previous attachment to

the story, rejoice! We have found an earth-shatteringly beautiful new voice in

historical fiction—resplendent with passion and poetry. A perfect voice for excavating the little moments

in humanity against the bleak brutality of Nerchinsk.

And then, the descriptions (music!) “ Hodel admired how the broadness

of his shoulders curved above the volume as if he were cradling the very

thoughts upon the pages with his entire body.”

“How exquisitely Nerchinsk sulks upon its gray and sorrowful

bluff. How shafts of sun burst through the thick, low blanket of cloud above

the village like stabs of hope from heaven.”

(ARE YOU KIDDING ME???? Dies of love)

And the feminism “Hodel saw it through her sister’s eyes:

women were created to be in every way partners, not mindless slaves or brainless

doormats, but helpers, collaborators, equals. And that was a thing of great

beauty”

And the simple wisdom “For our greatest rewards, Hodel,

sometimes we must endure.”

“Perchik could no longer stand being believed in—belief was

heavy; it was burning sunlight in his eyes.”

And this : “ I wanted a woman who was somewhat like the

moon. I would miss her when she was away and appreciate her when she returned,

but I did not want her around all the time!”

And this: “In two little words, all of Hodel’s life choices

were suddenly obliterated by Tzeitel’s sense of domestic superiority” ( snortle.

There are a lot of lovely sibling moments in this!)

No comments:

Post a Comment